Our goal is to maintain a low rate of car use in Dhaka (currently at 1%) by giving 15+ million people access to useful information about car-free mobility options. We believe that information can be a powerful catalyst for improving service, safety, and accessibility, and so the first step towards improvement in Dhaka is to provide information about buses to riders.

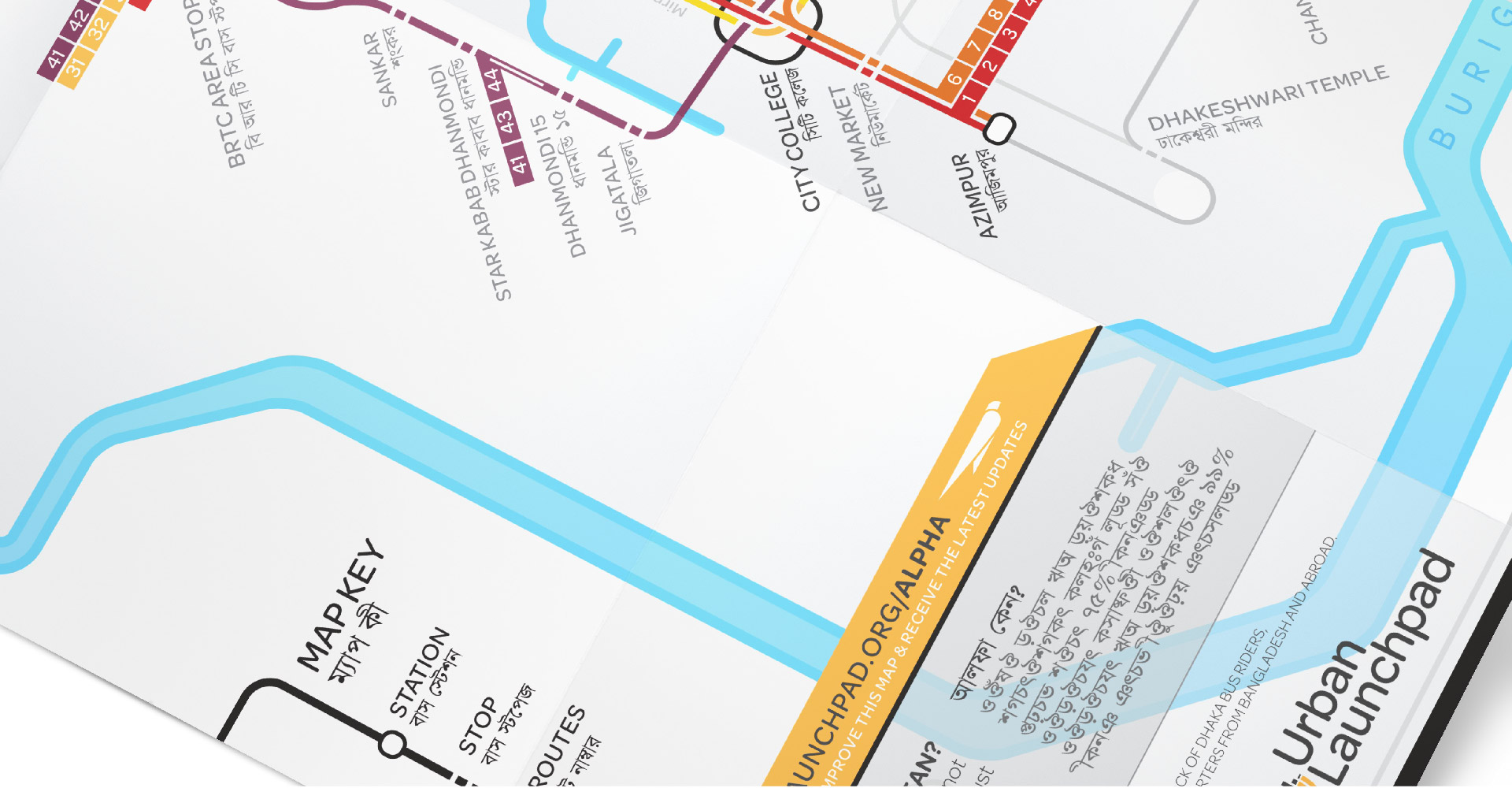

This project enlists local volunteers to help chart the city’s complex transit design and makes the map freely available to the public. A collaboration between MIT social-venture group Urban Launchpad and Bangladeshi advocacy organization Kewkradong hopes to bring transparency to public transit in Dhaka.

See our story on the stage at TEDxDhaka 2013

There are very few bus stops and no explanatory signage. Riders must jump on and off the bus while it is moving — all while avoiding chaotic streets crowded with people, cars, and rickshaws. Notice that while the road is full, half the space is reserved for rickshaws and pedestrians, modes which occupy less space and cause less pollution than cars.

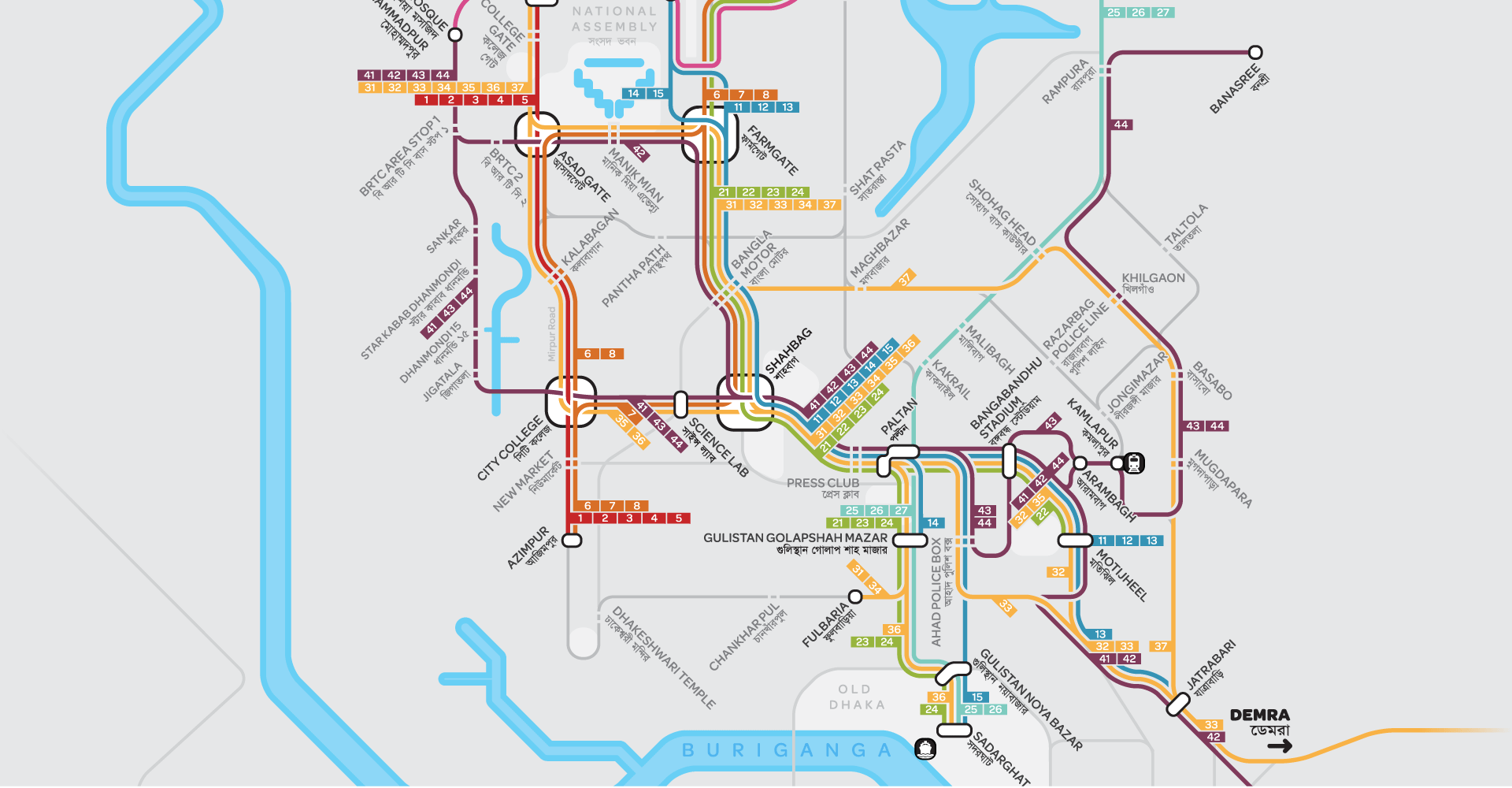

The idea is pretty simple – instead of collecting data with pen and paper, send out “flocks” of smartphone-equipped volunteers onto the city’s bus routes to record stops, arrival times, traffic patterns, and crowding levels.

Smartphones are equipped with at least 15 sensors including GPS and other location-sensing technologies. This allows us to more easily, and sometimes more precisely, capture the experience of riding a bus. The flock is really important because they are the most vital sensor, the one that can survey the other riders and understand not how a bus performs on the road but also for the people in which it serves.

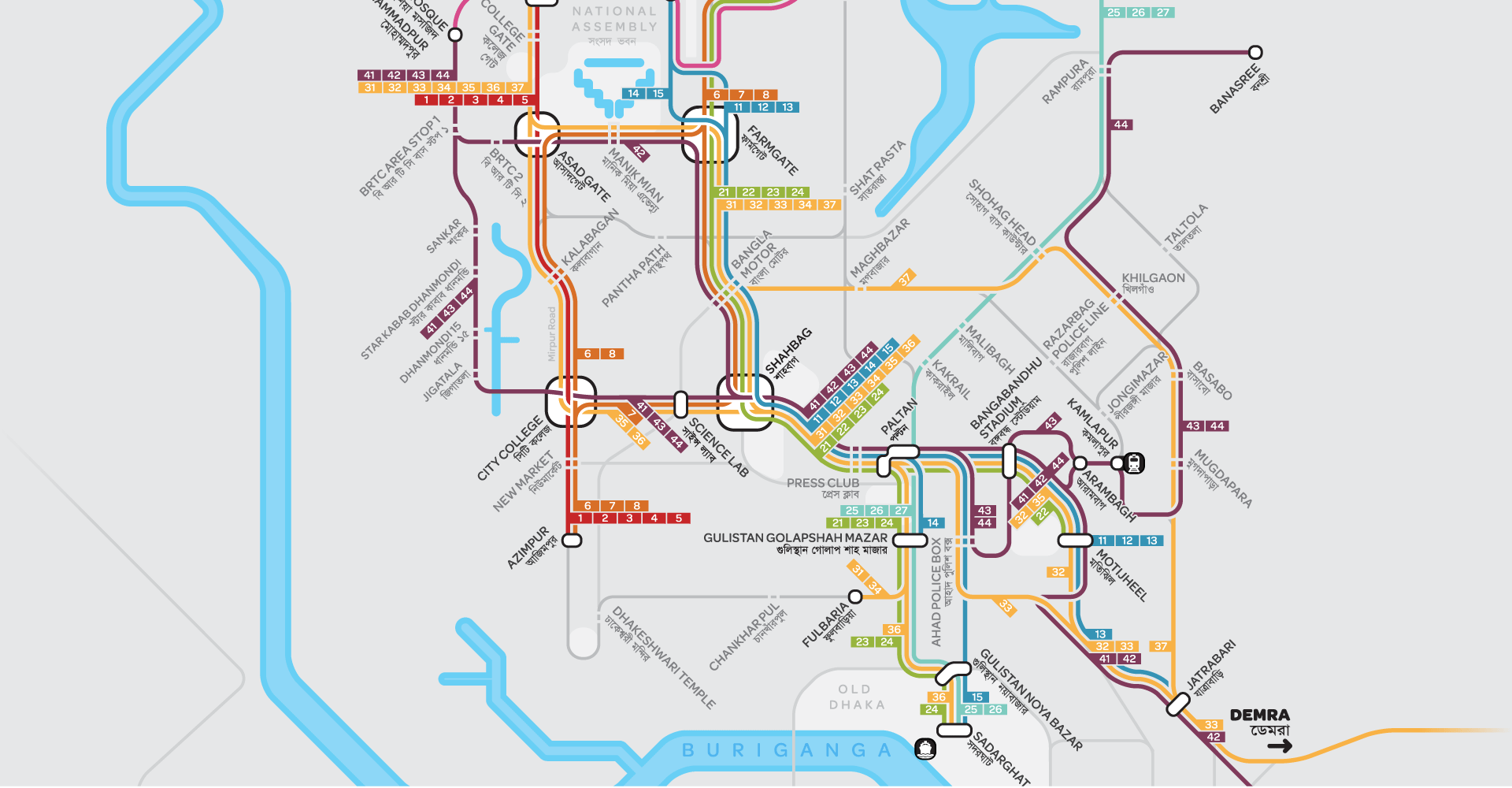

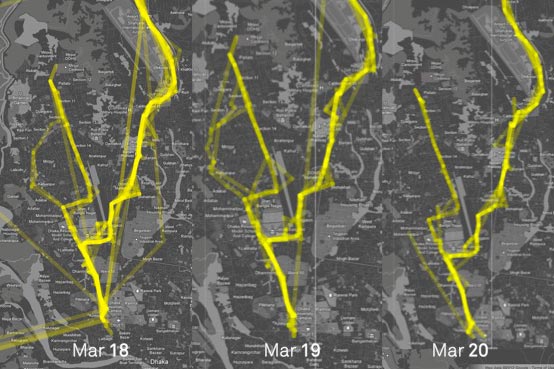

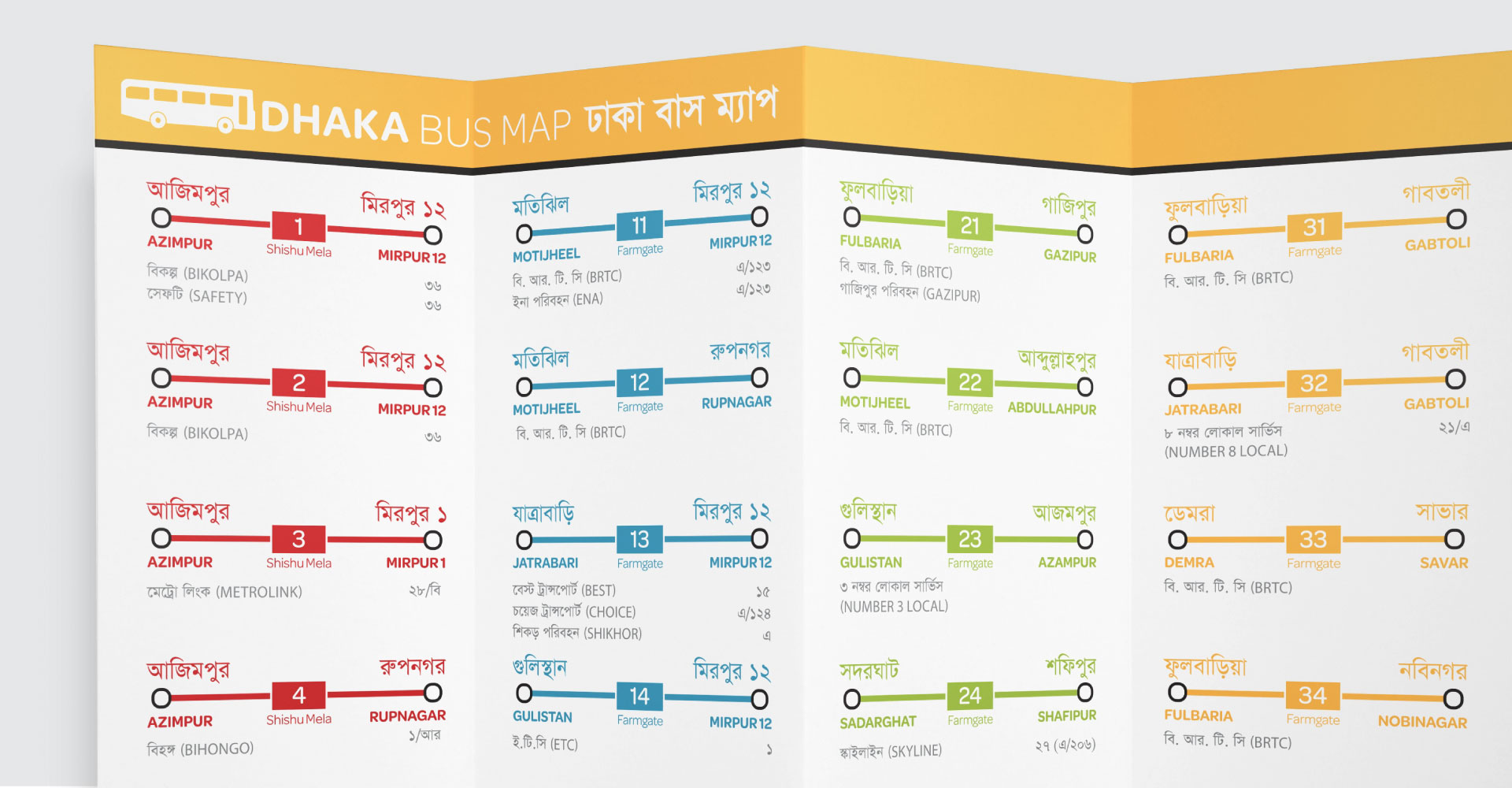

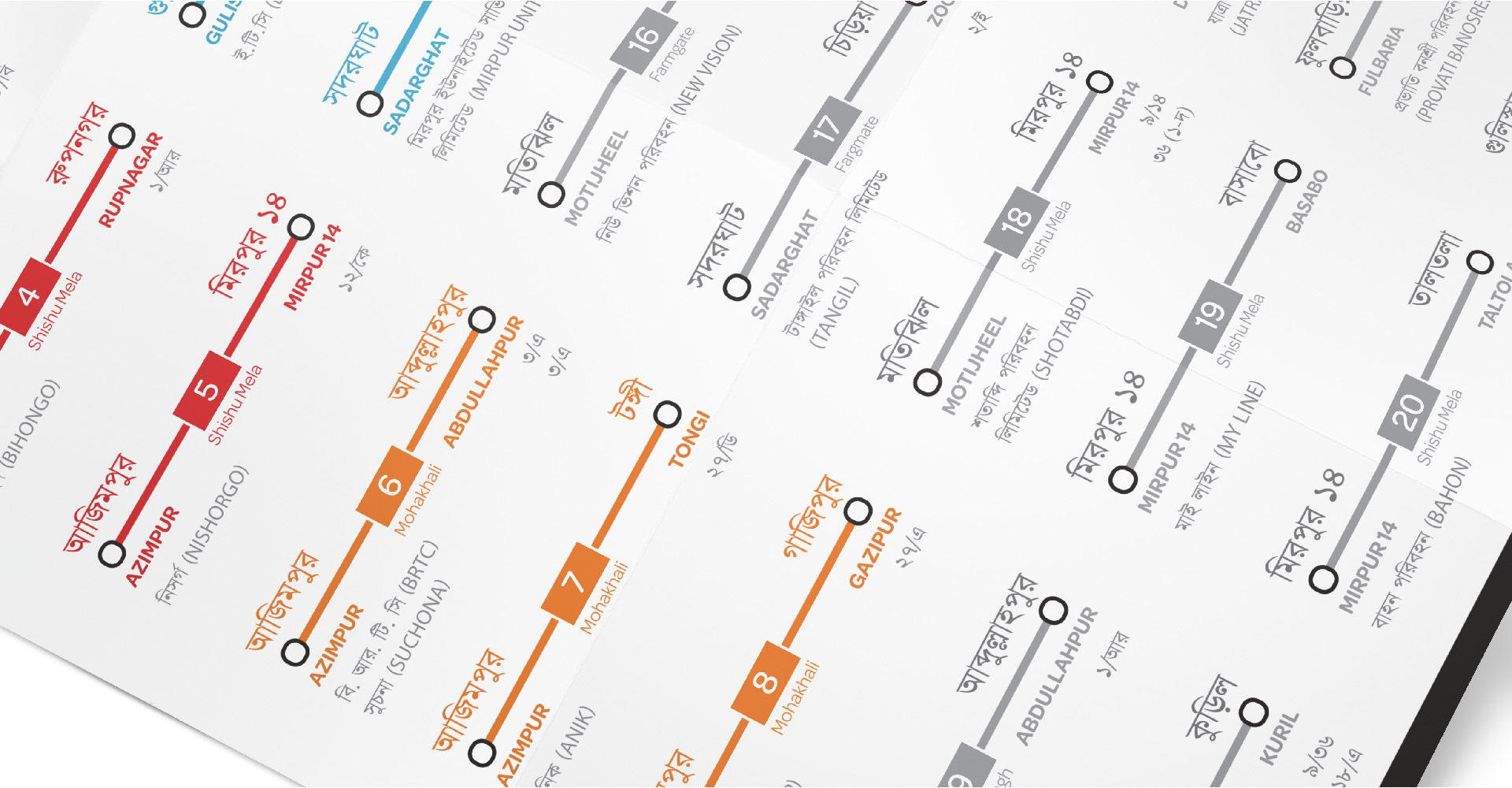

Without organization in the system itself, it took us awhile to figure out how to structure the bus information in a way that was useful to riders. So we had to start simple, noting the major directions and destinations in the city.

But once we visualized the flocksourced routes, we realized just how complicated the system was. This geographically accurate representation was obviously far too complicated to interpret, especially in the densest parts of the city, near Motijheel.

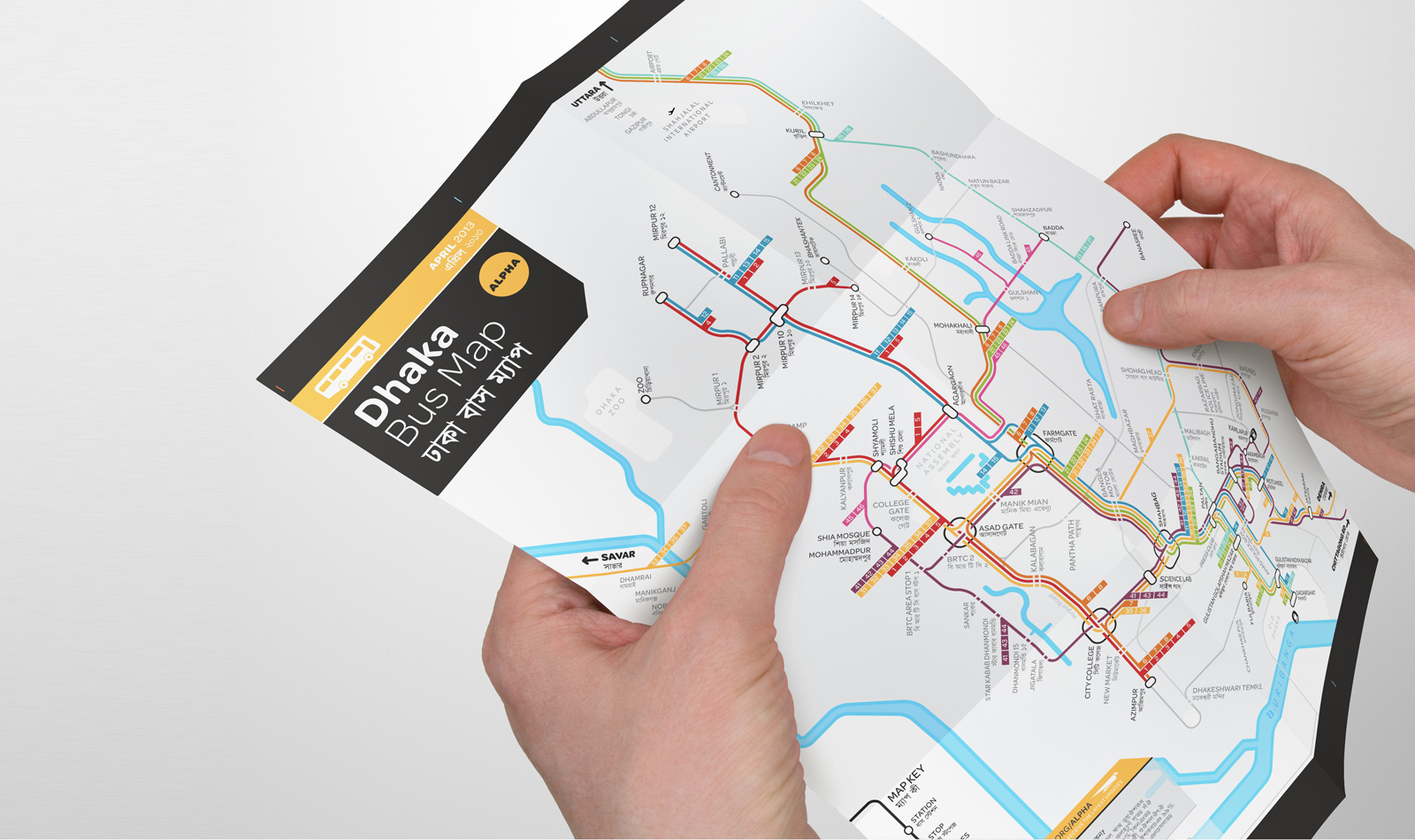

We decided to switch to a more diagrammatic take on the routes. While still providing some spatial context, this allowed users to focus more on key destinations and stops throughout the city. In the final alpha version, we color coded groups of routes and added labels and landmarks.

Later that summer, we were able to do an initial print run of 5,000 paper maps, which we distributed at various sites throughout the city.