Informal Transportation Networks in Three Indonesian Cities

Surakarta (Solo) and Jogjakarta, Central Java, Indonesia; Palembang, South Sumatra, Indonesia

This study focuses on three modes of informal public transportation (IPT) — the becak (three-wheeled pedicab), angkot (share taxi) and ojek (motorcycle taxi) — in Solo, Jogjakarta and Palembang, three midsize Indonesian cities. In this report, Kota Kita, along with the Cities Development Initiative for Asia, examines the various advantages, disadvantages and opportunities of each form of transportation in the three cities, while presenting various case studies and interviews with residents in order to identify strategies for improving mobility options.

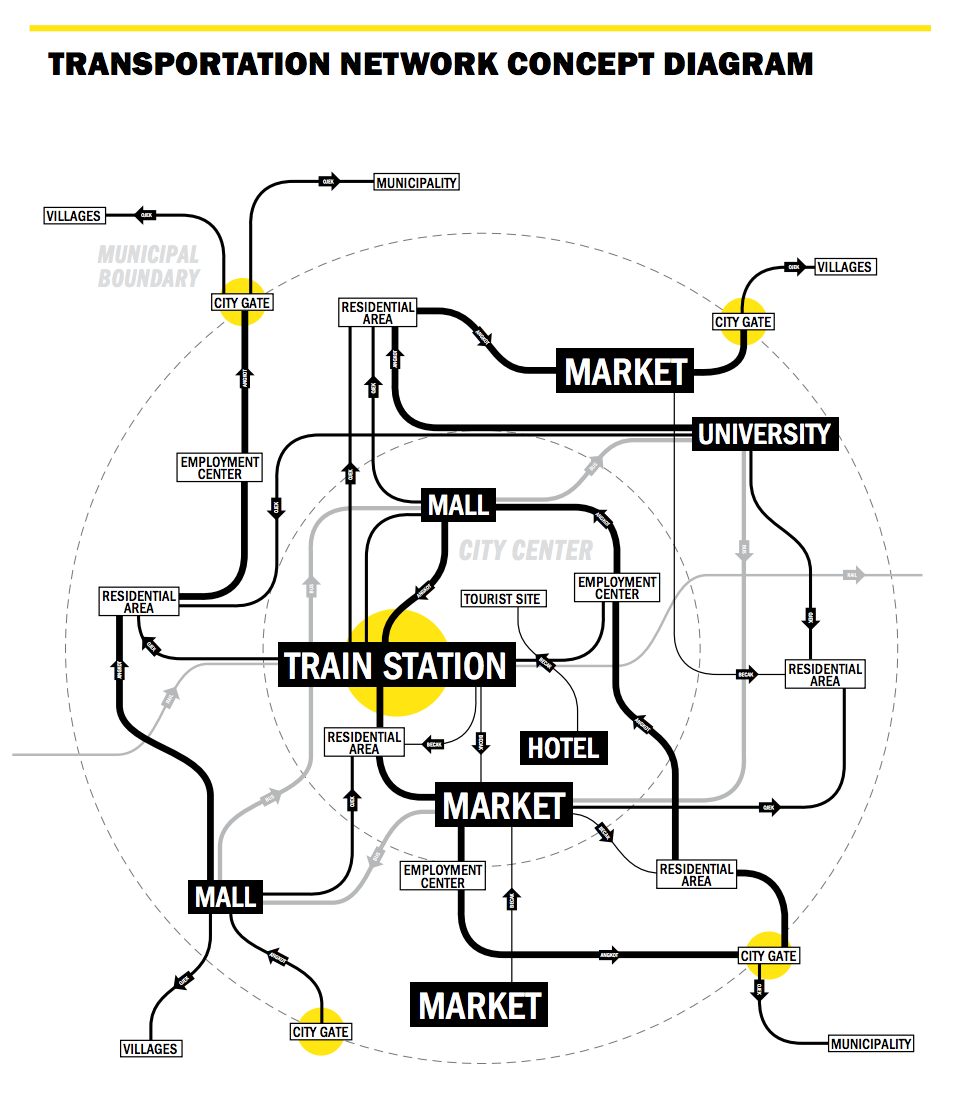

We found that informal public transportation providers create tremendous value for the overall urban transportation system, especially for the urban poor, whose needs are often not well served by formal transportation. IPT operates not in isolation from formal public transportation, but as a flexible complement to public services. We suggest that the mobility needs of the urban poor can therefore be met by supporting and harnessing the solutions created by IPT providers, rather than by introducing new technologies or services.

As Indonesian cities today become more prosperous, the demand for mobility among the urban poor is rapidly growing. This growth — and the accompanying traffic — is not just confined to large megacities like Jakarta, but also medium-sized cities as well. However, since the growth and mobility in medium-sized cities are different from those of Indonesia’s biggest cities, the solutions that are needed are different as well. For instance, these cities have different kinds of relationships with neighboring municipalities and surrounding villages, and their home-based and cottage industries are growing at a different scale.

Through a thorough analysis of the transportation options available in each city — and how they are actually used — we found that IPT not only increases mobility but is also a provider of employment and are part of the backbone of these cities’ informal economies.

IPT offers potential alternatives to the negative stresses of growth on urban transportation systems, as well as innovative approaches to providing service to people in poverty.

This is because IPT is flexible — the drivers accommodate variety of demands and uses. It fills in gaps, in that drivers pick up where formal public transportation networks end and go where formal public transportation coverage is lacking. And lastly, IPT serves niches, as drivers adjust routes, fares and schedules based on needs of specialized user groups, including students, women, informal vendors and the elderly.

In addition to the different urban texture of migration of midsize cities, the fairly recent decentralization of urban management from national government to municipalities is increasingly placing responsibility for transportation on the shoulders of local leaders. However, local governments do not necessarily yet have the capacity to manage large-scale transit systems, such as bus rapid-transit, and such systems may not even be serving the needs of the poor.

Without support or investment from local government, IPT providers have developed an adaptive alternative to insufficient formal transportation, while serving as a flexible complement to formal transportation systems where they are available. We suggest that local government can support informal public transportation providers in very simple ways, by assisting in the creation of “transportation facilitators.” Developed independently by IPT providers, transportation facilitators are both built and non-physical small-scale strategies to facilitate connections between modes, create accountability to provide good service and increase safety.